Drawings from the Permanent Collection

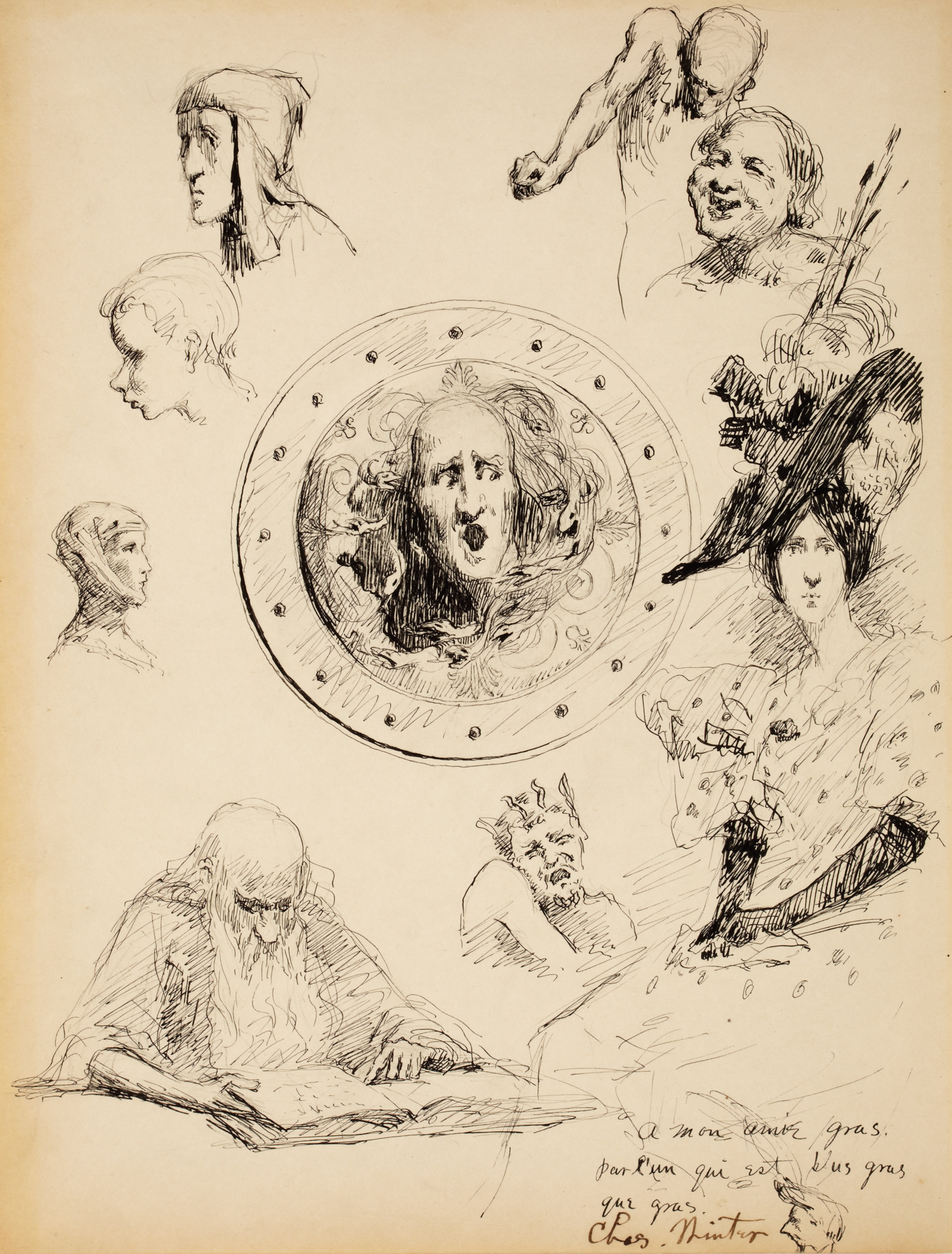

Drawing is one of the oldest forms of human expression, predating the written word. It has long been considered a fundamental part of visual art education due to its exploratory nature that allows artists to experiment and refine their artistic practice. Pulling together a selection of drawings and sketches from the Permanent Collection, this exhibition offers insight into the artists’ process and presents an opportunity to celebrate these sometimes overlooked works as artworks in their own right.

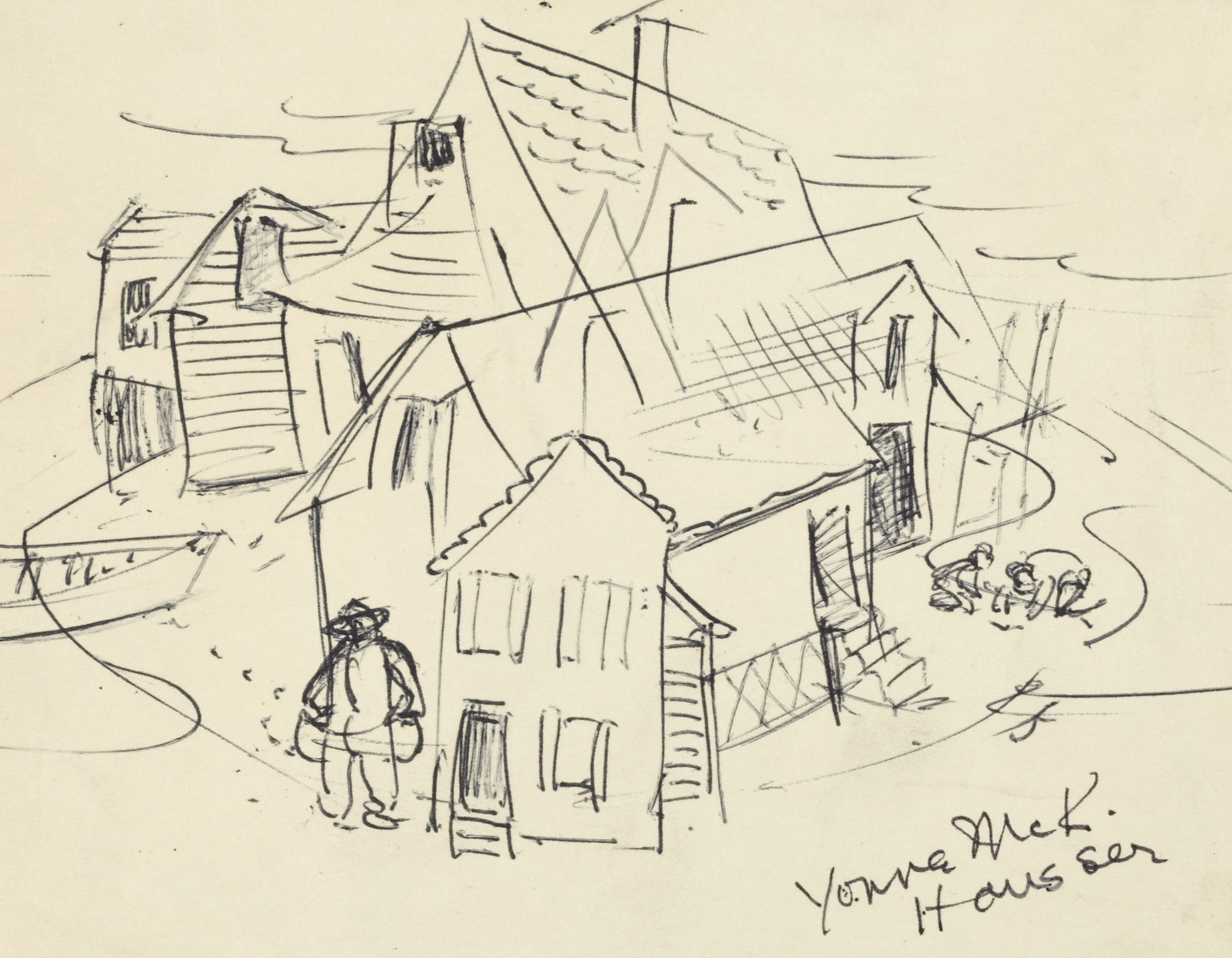

The portability of drawings and sketchbooks has made it a great method for observing the world. In Yvonne McKague Housser’s Walking with a Sketchbook, Mexico (n.d.), as the title suggests, the artist traveled with her sketchbook to capture her views and experiences. Another example is A.Y. Jackson’s Close-up Study of Rocky Shore with Puddle (n.d.), a double-sided sketch, which, based on the ring holes along the side, once lived in a sketchbook.

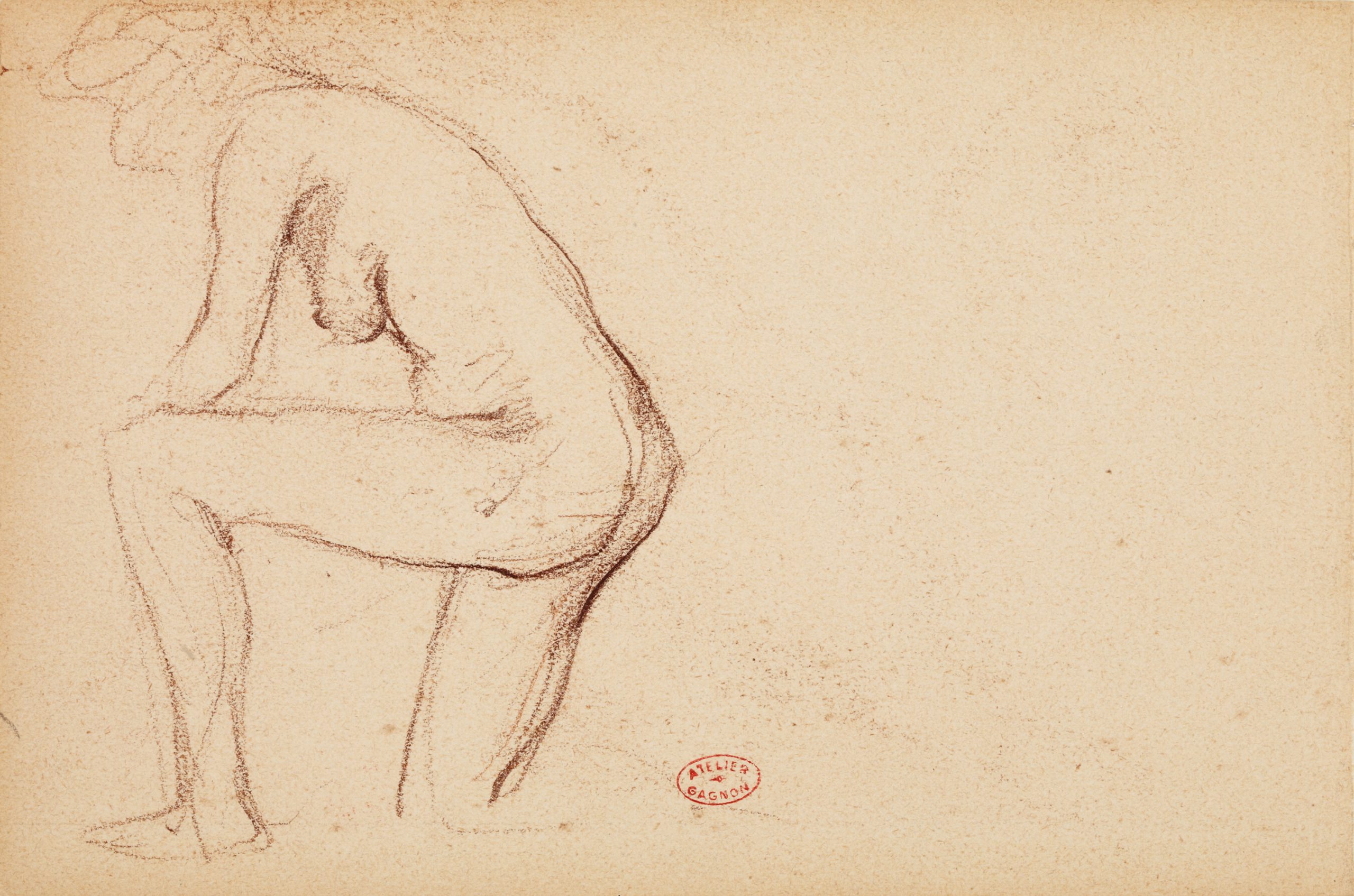

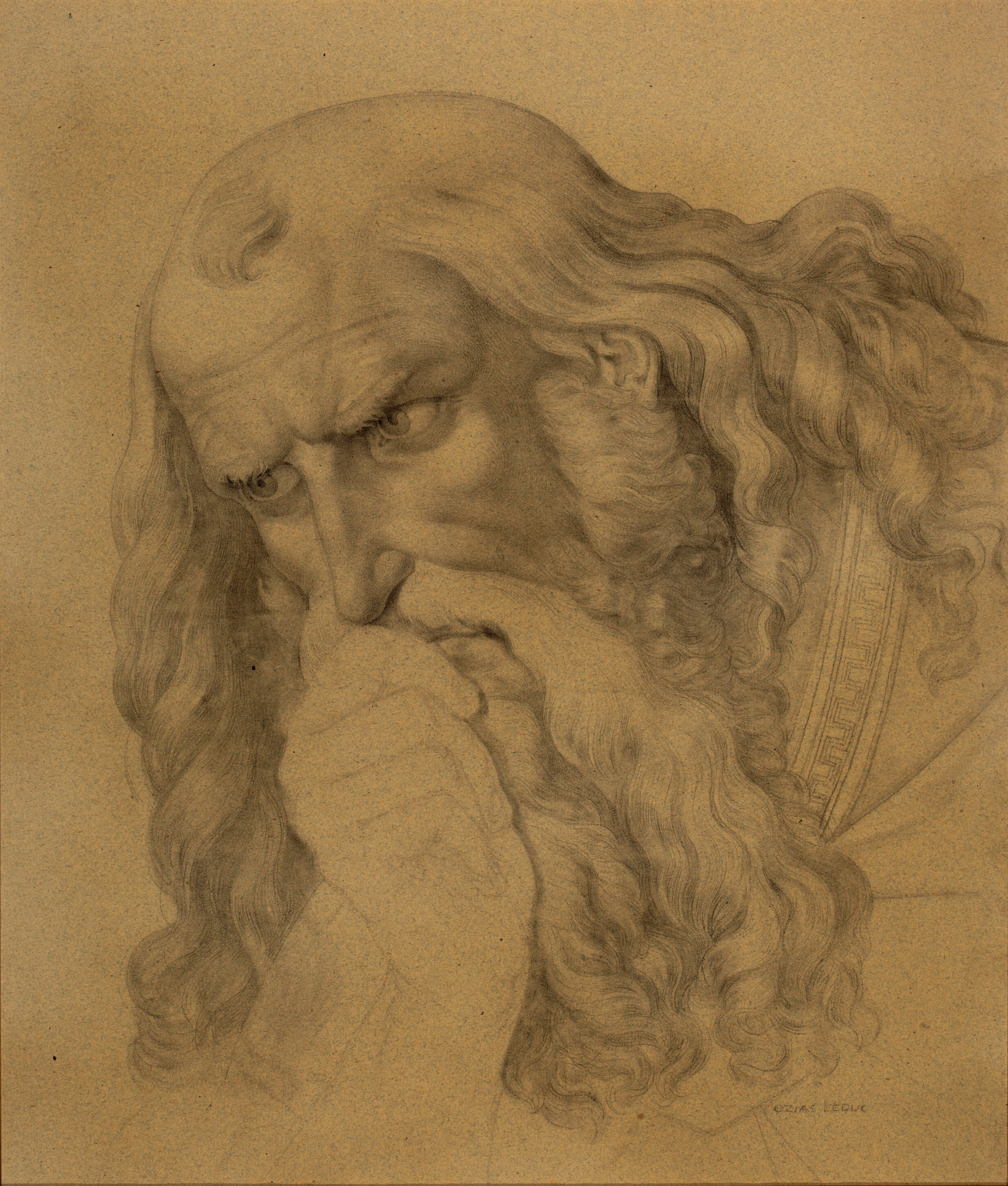

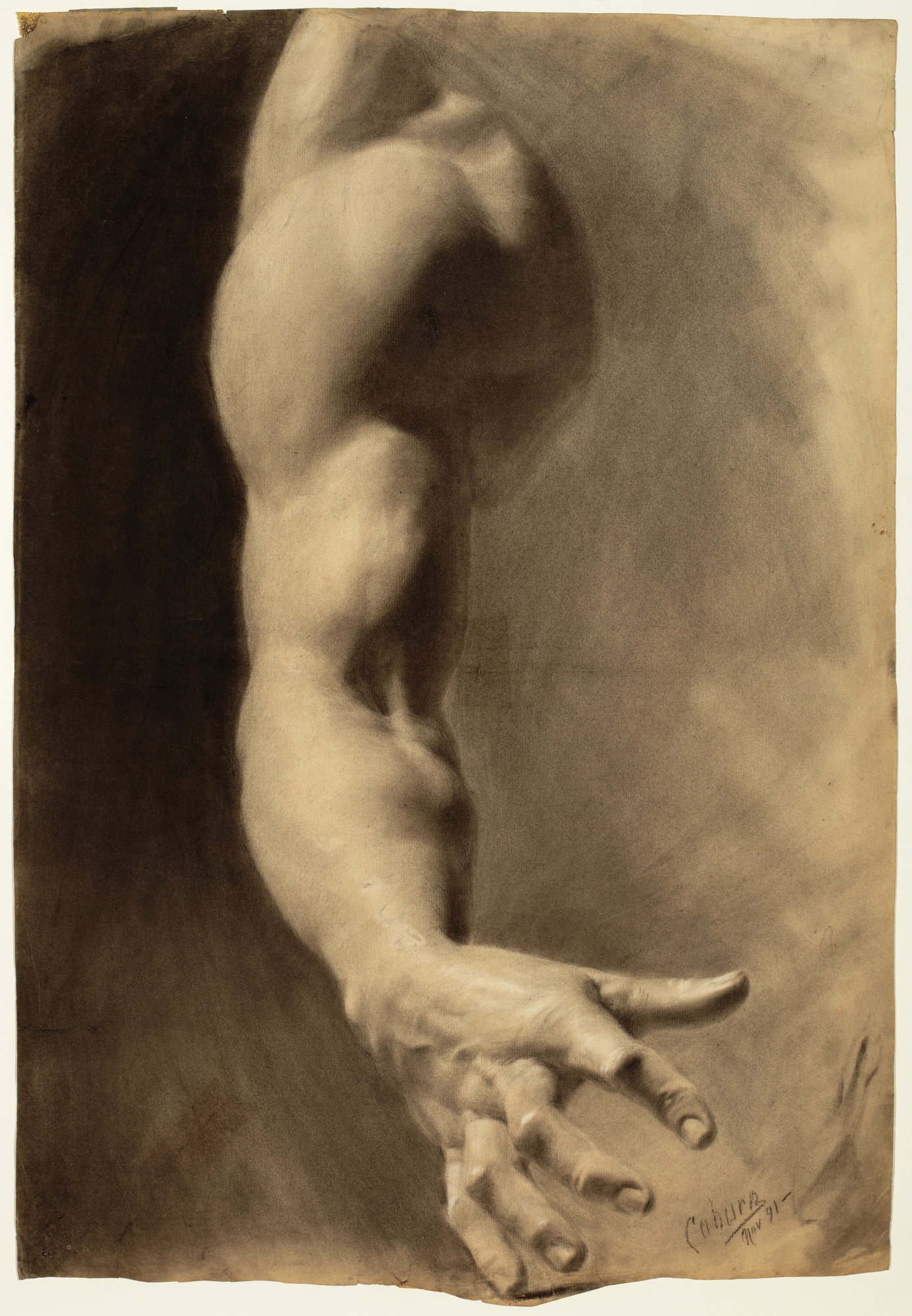

Some of the drawings in this exhibition are examples of artists exploring the human form. Anatomical studies were common for artists to practice and refine their ability to depict the human body. Two precise and very different examples are William Blair Bruce’s more scientific drawing of the tendons in the arm in Untitled (Anatomical Studies) (n.d.), and F.S. Coburn’s Power (1891), in which he uses charcoal to get the definition of muscles and veins through shading. These types of sketches demonstrate the medium’s ability to help artists’ further study, experiment, and improve techniques.

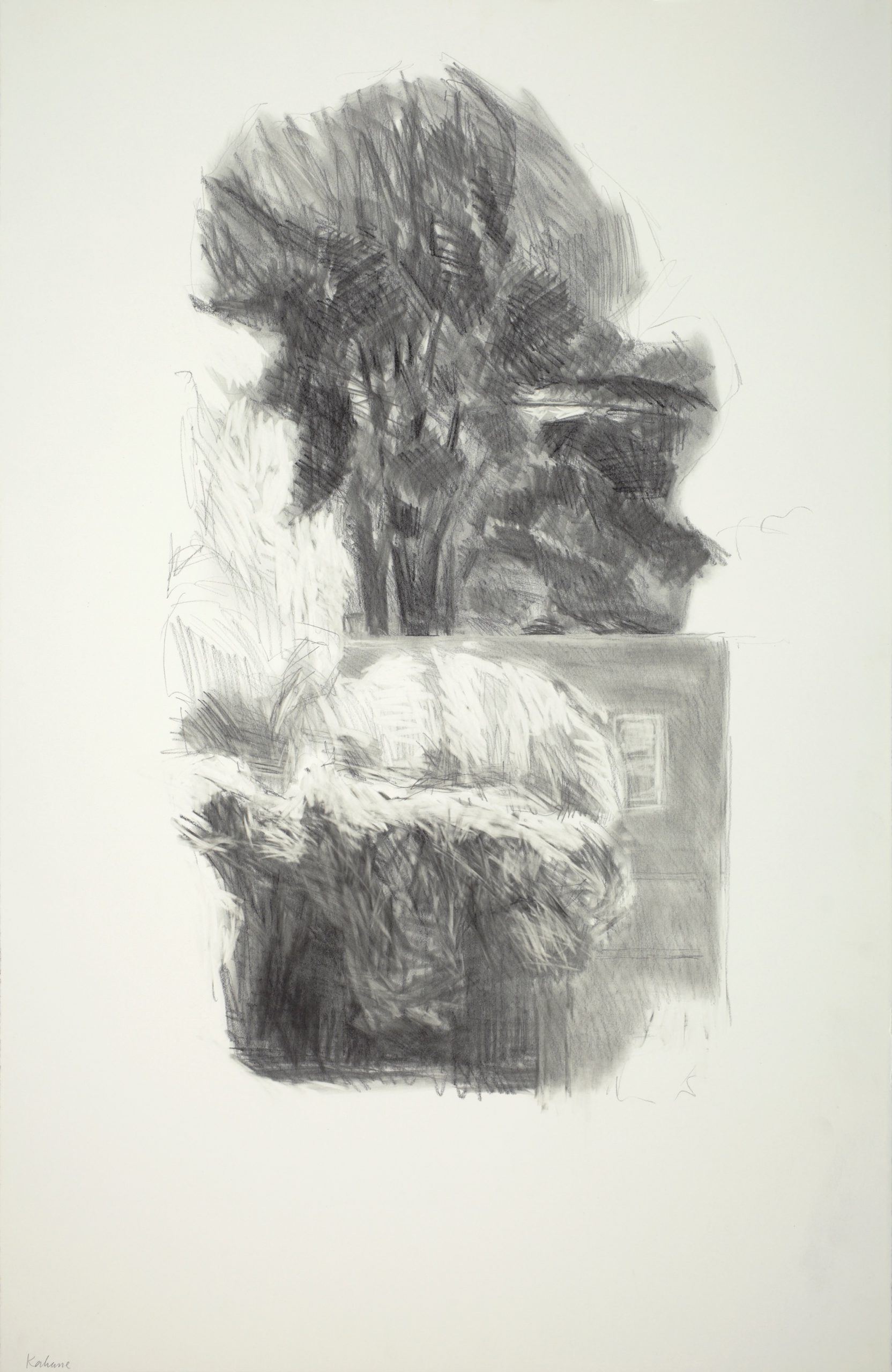

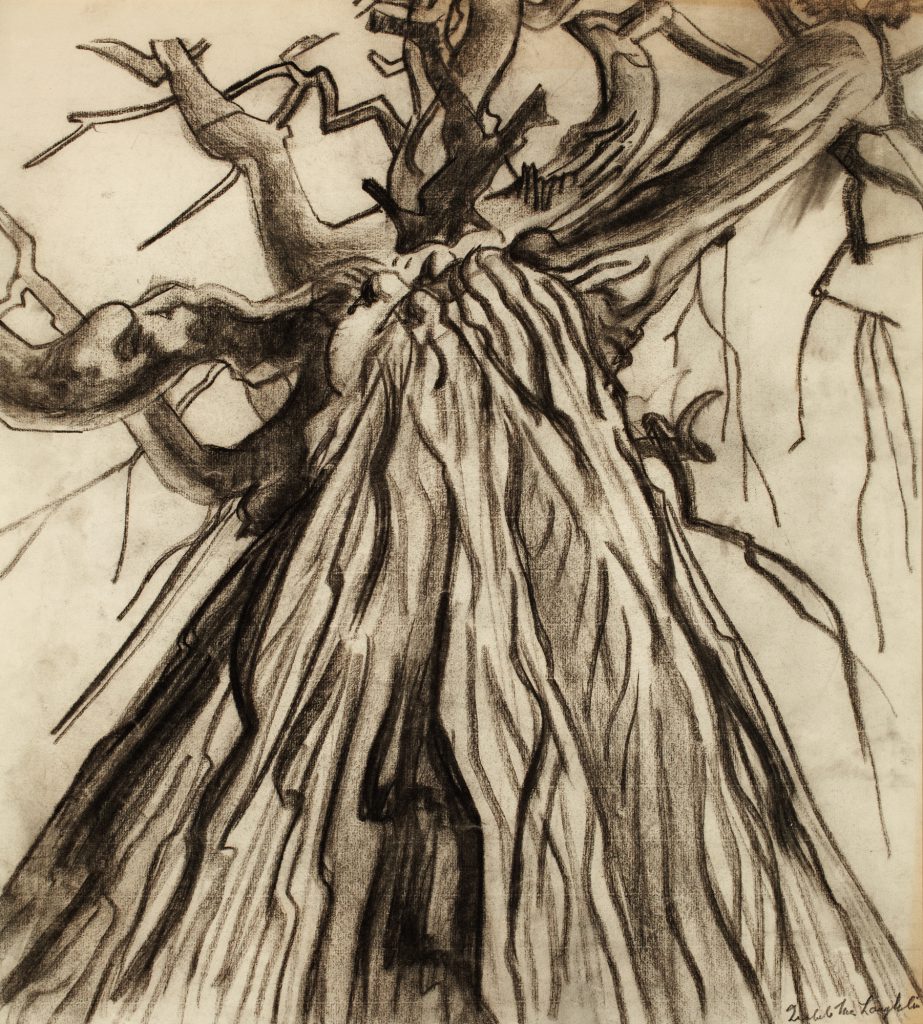

While some of the works in this exhibition are examples of quick drawing exercises, others are preparations for paintings and prints, called studies. Take for example, Isabel McLaughlin’s Sketch for Tree (c. 1935), which is the study for a large painting that is in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada entitled Tree (1935). McLaughlin did many preparatory sketches for this painting, but this one clearly shows the decisive approach that she ended up using for the final painting.

Isabel McLaughlin (Canadian, 1903-2002), Sketch for Tree, c. 1935, charcoal on paper. Gift of the estate of Isabel McLaughlin, 2003.

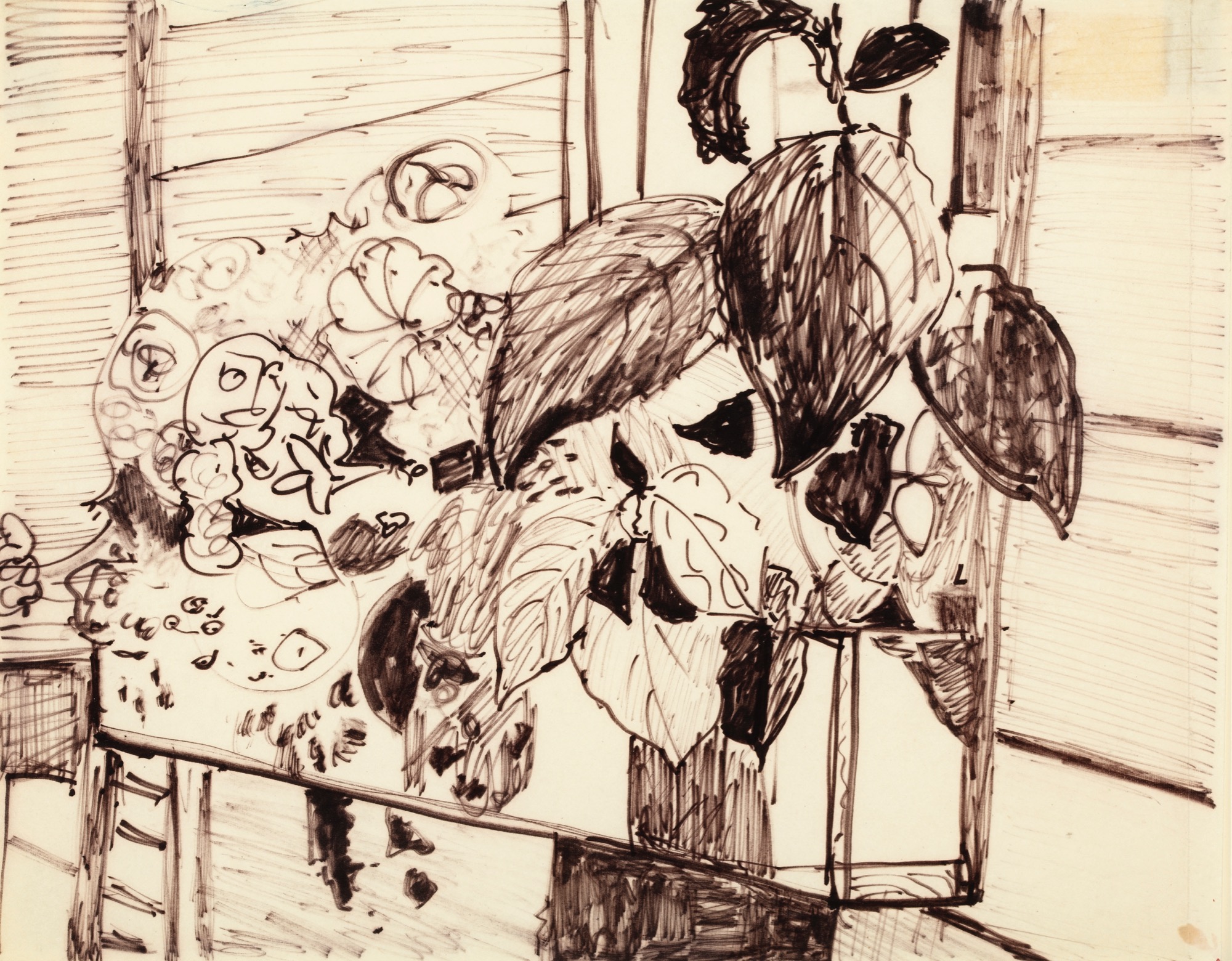

Arthur Lismer (Canadian, b. England, 1885 – 1969), Study for The Happy Isles, c.1924, charcoal on paper. Gift of Charles Goldhamer, 1984.

Arthur Lismer’s Study for Happy Isles (c. 1934) is another example of a sketch in preparation for a large canvas now in the collection of the University of Saskatchewan. It shows how Lismer structured and planned the composition and spacing of the painting. The study depicts Georgian Bay, affectionately referred to as Happy Isles, and captures Lismer’s interest in detailed foregrounds with the figures on the dock.

Drawing from both life and their imagination, artists use the medium to explore and experiment. As artist Paul Klee once said: “A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” The artworks included in this exhibition take us on a journey with the artist and show how drawings are not just simply a step in the creative process, but can be enjoyed as individual artworks in and of themselves.